Minnesota’s first Black-owned bank

The murder of George Floyd sparked calls for businesses to address racial bias in their communities. Answering that call, Wells Fargo and other large Minneapolis banks worked with First Independence to open Minnesota’s first Black-owned bank.

There’s a new logo on the sign outside, but Damon Jenkins hasn’t changed where he comes into work each day. Why he comes in has changed. Just a year ago, he was a Wells Fargo district manager. Today, in the same building, Jenkins leads a new Minneapolis branch of First Independence Bank, the first Black-owned bank in Minnesota. Located in the former Wells Fargo branch, the bank is part of a greater vision to expand banking and support the financial growth of underserved communities.

For Jenkins, who moved to south Minneapolis over 30 years ago, joining First Independence Bank means effecting change, especially for Black residents in his community. This is vital work, he says, given the city’s racial reckoning following the 2020 murder of George Floyd and the uneven financial recovery from the pandemic.

Following Floyd’s murder, Jenkins prayed for a way to do more.

“A lot of the unrest was in my own backyard, so I felt obligated to lean in and do my part,” he said. “This opportunity [to join First Independence Bank] really aligned with my why. This partnership is my opportunity to get closer to and be a part of an unprecedented ecosystem where we’re trying to bring equity to underserved and unbanked communities. Being that George Floyd’s murder took place here … this is a time for us to really rethink how we meet people where they’re at and allow them to have resources, but also give them access and power their potential.”

With the encouragement of his former Wells Fargo peers, Jenkins now serves as the head of the new branch, which opened in February and held its grand opening April 26.

"… this is a time for us to really rethink how we meet people where they’re at and allow them to have resources, but also give them access and power their potential.” — Damon Jenkins, head of First Independence Bank Minneapolis branch

The branch became possible through unique partnerships between First Independence Bank and five large banks in Minneapolis: Wells Fargo, U.S. Bank, Huntington Bank, Bank of America, and Bremer Bank.

“I’ve been a banker for 15 years and was working at one of the largest firms in the industry. I have a lot of reach, and we [at Wells Fargo] know that we’ve really been able to power the potential of folks. But having grown up in Minneapolis, I saw the people who needed resources,” Jenkins said. “That’s why the mission these six banks were trying to accomplish made sense.”

Building ‘a muscle in the community’

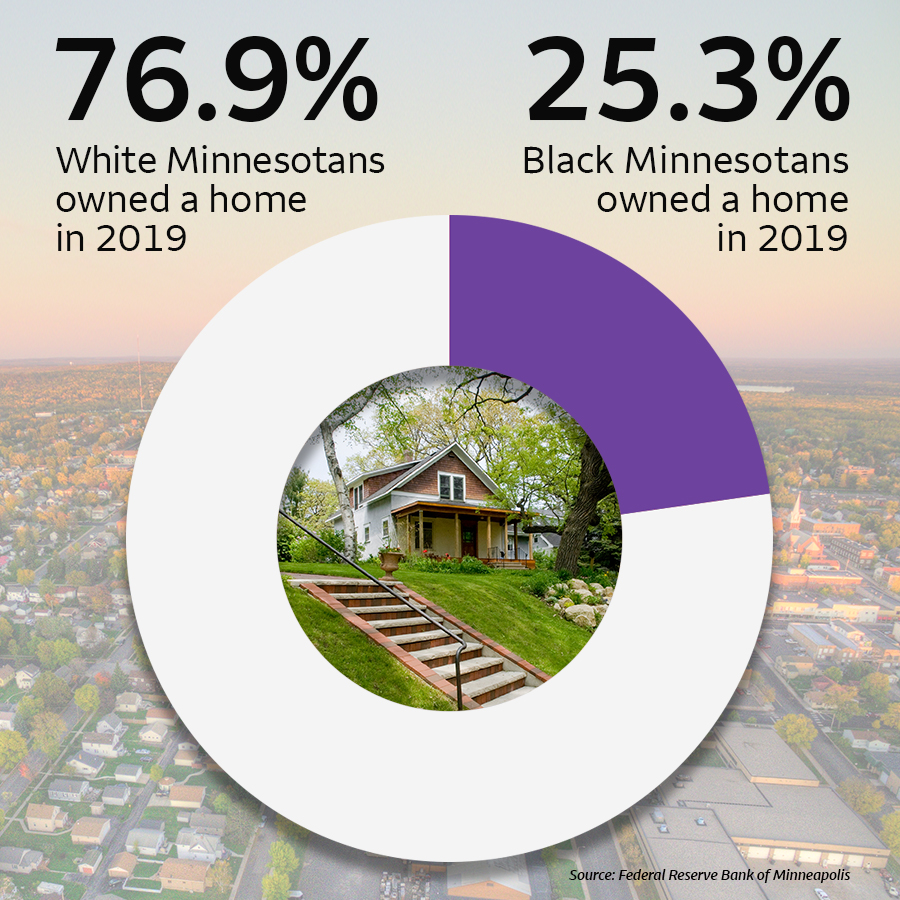

Minnesota has the largest homeownership gap in the nation (76.9% of white Minnesotans owned a home in 2019 versus 25.3% of Black Minnesotans), and the median net worth was $211,000 for white households and $0 for Black households in 2019, according to an analysis published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

In 2020, following Floyd’s killing, Laurie Nordquist, who retired in April as Wells Fargo’s regional banking executive for the Central region, frequently gathered with colleagues at major banks in Minneapolis to address the area’s racial disparities in wealth and homeownership. Nordquist and her colleagues decided to partner with a Black-owned minority depository institution, or MDI.

First Independence Bank’s expansion to Minnesota represents a powerful growth in the footprint of Black-owned banks and other MDIs whose numbers have steadily decreased for many years.

“Looking at the wealth gaps, they’re stark. Quite frankly, the gap is so big, we need more [banks], not less,” Nordquist said. “The goal was to do something that the five banks couldn’t do individually. Everyone is contributing. We aren’t at the table as competitors. We’re at the table as leaders in the market concerned and wanting to make a difference.”

The plan came together organically. Wells Fargo already had strong connections with many MDIs. In 2020, the company pledged $50 million to 13 Black-owned banks, including First Independence Bank, which was weighing expansion opportunities. Wells Fargo wasn’t using a former branch in Minneapolis’s Prospect Park neighborhood. Plus, it was especially valuable for a bank because of its drive-thru, which is barred in new construction in Minneapolis.

Wells Fargo donated the building to Project for Pride in Living, or PPL, a Minneapolis-based nonprofit that has collaborated on workforce training and other projects with Wells Fargo for decades. PPL now owns it and leases space to First Independence Bank.

“A Black-owned bank is like a muscle in the community. You need to have that muscle to build a strong and vibrant African American community,” said Paul Williams, president and CEO of PPL. “Certainly, coming out [of the murder] of George Floyd, we know how desperately we need that.”

The partnership includes:

- First Independence Bank customers have access to Wells Fargo ATMs with no fees.

- Wells Fargo is helping to build the bank’s loan assets.

- Company leaders are connecting First Independence Bank to stakeholders across the state.

- Wells Fargo is assisting with capital, research, marketing, and other services.

“If we can bring in those communities where trust and a very specific local presence [have been lacking], then we’re truly opening up the financial industry to many more people who otherwise might not be in it or choose not to be in it because they didn’t have that specific bank. The more people we can get into the banking system, the better.” — Danielle Squires, Wells Fargo head of Corporate and Investment Banking’s diverse segments

Danielle Squires, Wells Fargo’s head of Corporate and Investment Banking’s diverse segments and whose team covers MDIs, describes this as part of the company’s continued investment of “time, talent, and treasure” into MDIs.

“If we can bring in those communities where trust and a very specific local presence [have been lacking], then we’re truly opening up the financial industry to many more people who otherwise might not be in it or choose not to be in it because they didn’t have that specific bank,” she said. “The more people we can get into the banking system, the better.”

‘A beacon of hope’

The bank arose from one of the darkest days of Detroit’s history: the deadly 1967 riots. At the time, the city faced growing tensions between Black residents and police on top of financial hardship from its waning auto industry. During the uprising, 43 people — mostly Black residents — were killed and hundreds of fires burned. Many families formed a plan to rebuild, and First Independence Bank opened in May 1970 to serve Motor City’s Black residents.

Jenkins sees some of these tensions in Minneapolis today.

“When you go deeper and look at the root causes [of Detroit’s riots], it’s parallel to what we saw here in Minneapolis with the killing of George Floyd — police brutality — but the true root causes stem from systemic racism and all those other inequalities that marginalize folks, especially people of color,” he said.

Prospect Park, where First Independence Bank operates today, has its own unjust history.

“This branch is a beacon of hope for Black and minority communities. When you walk into a bank and sit across the table from someone who looks like you, it’s a different sense of comfort. I have a vision that’s beyond just bringing services to unbanked and underbanked communities in the Twin Cities. We’re talking about across Minnesota.” — Damon Jenkins, head of First Independence Bank Minneapolis branch

In 1909, when the first Black family moved to the neighborhood — a few blocks from the branch today — more than 100 white residents protested. The ensuing “race war,” as local newspapers reported at the time, led to racial covenants restricting what homes nonwhite residents could occupy. Across the country, such discriminatory practices were institutionalized via a practice widely known as redlining, where banks would not lend to Black or minority homebuyers in predominantly white neighborhoods.

While First Independence Bank serves all customers, the bank has long-term goals of addressing racial disparities in Black homeownership and financial literacy in the Twin Cities. The bank is building on the momentum of the first branch with a second location near Lake Street and Hiawatha Avenue, an area of south Minneapolis that is still recovering from unrest following Floyd’s killing. That branch is expected to open in November.

Many may simply see a bank in Prospect Park, but others, like Jenkins, see far more than its four walls.

“This branch is a beacon of hope for Black and minority communities. When you walk into a bank and sit across the table from someone who looks like you, it’s a different sense of comfort,” he said. “I have a vision that’s beyond just bringing services to unbanked and underbanked communities in the Twin Cities. We’re talking about across Minnesota.”