Wells Fargo mural honors bravery of Freedom Riders fighting segregation

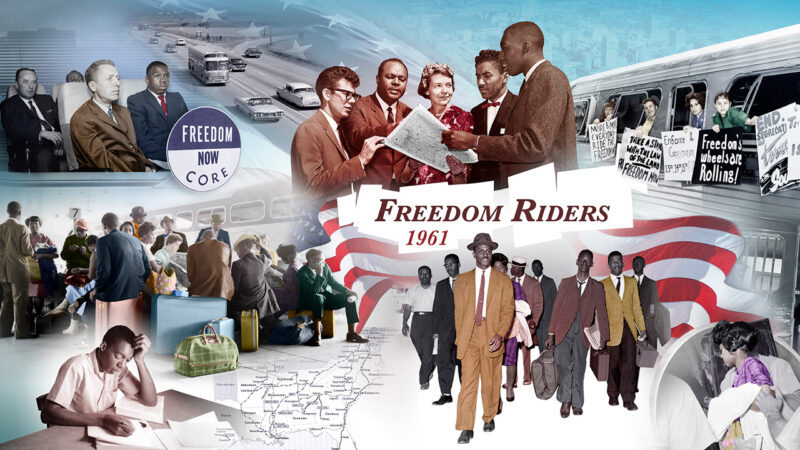

In 1961, segregation was illegal on interstate public transport, but the law was ignored in the Deep South. A Wells Fargo mural in Birmingham, Alabama, tells the story of the Freedom Riders who put themselves at risk to uphold the law.

Watch the Freedom Riders video

At 6’4” and 240 pounds, 19-year-old Hank Thomas was unaccustomed to being confronted. That changed on May 14, 1961, when he found himself facing a crowd of Ku Klux Klansmen in Anniston, Alabama. The mob — armed with chains, lead pipes, and baseball bats — shouted insults, broke windows, slashed tires, and ultimately firebombed the bus he was riding.

![Picture of Hank Thomas and quote: I felt that would be my last day. I knew if I got off the bus, I would be beaten to death. But if I stayed on the bus, [I was] gonna be killed by the fire or the smoke.](https://stories.wf.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Birmingham_mural2_HT_inline_900x527a.jpg)

“I felt that would be my last day,” Thomas said. “I knew if I got off the bus, I would be beaten to death. But if I stayed on the bus, [I was] gonna be killed by the fire or the smoke.

“I had to decide: Which way was I gonna die?”

Thomas survived — only to be attacked by a man wielding a baseball bat. Despite having a concussion, he rejoined the Rides in Montgomery, Alabama. Ten days later, he was arrested in Jackson, Mississippi.

Despite the danger he knew he could face, Thomas was on those buses by choice. He was one of 13 original Freedom Riders who volunteered with the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, to challenge segregation in the Deep South.

The bravery demonstrated by Thomas and the other Freedom Riders is illustrated in a Wells Fargo mural in Birmingham, Alabama. The Wells Fargo Community Mural Program team worked on the project for over a year, delving deeply into the history of the rides. “I don’t think you could overstate the spotlight that the Freedom Rides shone on what was happening,” said Wells Fargo Historian Marianne Babal. “These injustices were ongoing, but they were kind of invisible to a lot of people. The rides really brought it into public consciousness.”

Freedom Riders took a stand despite danger

Segregation was already illegal on interstate public transportation, including terminal lunch counters, waiting rooms, and restrooms, yet the law was ignored in several Southern states. Freedom Riders — men and women, Black and white, young and old — united to uphold the law, even though it meant putting themselves at grave risk.

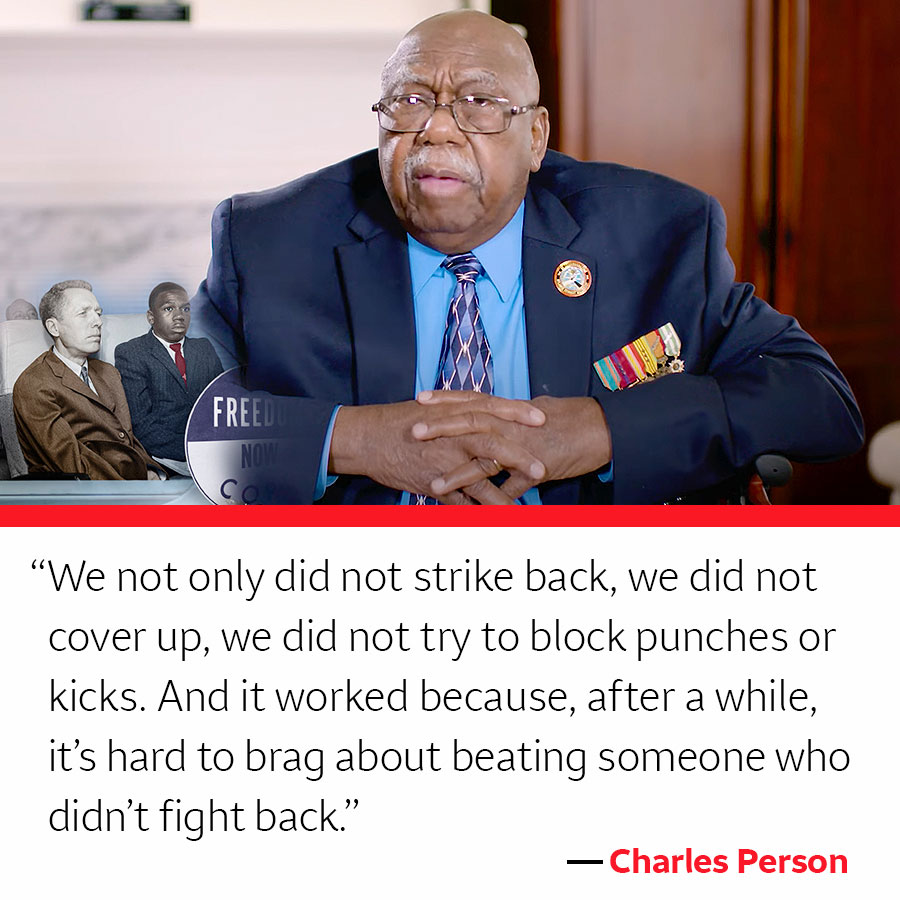

“This was not an act of civil disobedience, because the law was in our favor,” said Charles Person, who at 18 was the youngest of the 13 original Freedom Riders. “The law had already been passed that said we could use these facilities.”

Because he was so young, Person needed his parents’ permission to participate as a Freedom Rider — an experience that would shatter the remnants of his childhood innocence.

Person and fellow riders were warned of violence in Alabama. When we got to Birmingham, Person faced a wall of men preventing him from sitting at a whites-only lunch counter. He was struck in the head with a lead pipe that left a knot the size of a fist. Fellow rider James Peck and a photographer on the scene were also severely beaten.

“I grew up overnight,” Person said. “I had never experienced that level of violence. The people, their faces were contorted with hatred. And I couldn’t understand in my youth: How could you hate me so much? How could just my very presence generate that kind of animosity?”

Riders kept true to principles of nonviolence

Before setting out on the rides, CORE prepared the original 13 Freedom Riders with nonviolence training and role-playing in anticipation of scenarios they could encounter.

Person said training stressed that “you would remain nonviolent no matter what happened to you — whether they spit on you, or they yanked you off a stool, or squirted condiments on you, or even put a cigarette out on you. That was about the extent of what we thought might happen to us.”

The resistance and hatred they faced were beyond what they imagined, but despite the level of aggression and violence the riders were met with, they held true to their training.

“We not only did not strike back, we did not cover up, we did not try to block punches or kicks,” Person said. “And it worked because, after a while, it’s hard to brag about beating someone who didn’t fight back.”

Following the Anniston firebombing, CORE decided to discontinue the rides. Catherine Burks-Brooks and other Nashville student activists decided to continue them on their own. This growing army of supporters — both Black and white, including a significant number of Jewish activists — played an integral role in the success of the effort. Before the year was out, over 60 Freedom Rides had been organized, and some 400 riders from across the country had joined in.

Mural captures extraordinary effort to change history

The mural was unveiled on May 4 to coincide with the 61st anniversary of the first Freedom Ride. Located at the former site of Wells Fargo’s Birmingham Tower Motor Bank, which was constructed on the grounds of the old Trailways bus depot where Person and other riders were attacked, the artwork captures the courage, the determination, the coordination, and the history of the Freedom Riders.

After the unveiling, Burks-Brooks shared the story of how she and her friends were inspired by the events in Anniston and Birmingham. She also recounted how she and the others persevered to ensure the rides could continue.

“What was accomplished with the Freedom Rides and the hundreds of people joining them in the course of that year, it’s pretty remarkable,” said Melanie Tobin, Wells Fargo researcher. “It’s one of those direct-action initiatives that shows we can change history, change society for the better.”

The Freedom Riders mural, created by Wells Fargo graphic designer Anne Marie Lapitan, “shows the quiet moments, the contemplative moments, the determined moments, the arrests,” she said. She hopes the mural inspires viewers to be informed, to support communities, and to speak up to do what’s right — just as the Freedom Riders and other peaceful protestors have done.

“The sit-ins, the Freedom Rides, and the other acts are what helped changed this country. Sixty years ago, we were doing things that made it possible to have a Black man as president, a Black woman as vice president, a Black man as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the whole situation with reference to Black folks today is a world of difference to what it was 60 years ago,” Thomas said. “So it was worth it. It was worth it.”